Notism Movement

Notism art exalts the Beauty of Memory. It’s symbolic of primal loss; the fading reality of nature’s perfection. These hieroglyphic scribbles and scrawls manifest in a unique pictorial language that reflects urgent efforts to preserve our personal histories and rapidly fleeting histories.

It symbolizes our attempts to form a connection between internal memory fragments and nature’s raw symbols, textures, and colors. The haunting pain of life passing by is laid bare in textual writings that serve as metaphors for our past; a visceral loss of the profound feelings that accompany our recall of emotionally charged events.

Notism (“NO-tizm”) also assaults information overload and helps us preserve the organic power of communicating through intimate, hand-written notes.

notism statement continues at bottom.

The Artist in front of his "Notism: Mind Mapping" work, in the home of Harry Dubin, Palm Beach/FL.

"Red Orbs" 2018. Acrylic over pen and ink on paper. 11 x 8.5" (On exhibit @ Manolis Projects/Miami, April-May, 2022)

SOLD-"Mind Mapping" 2021. Acrylic, archival inks, enamel, oil paint pens on canvas. 70 x 54" (Private collection of Liz Dubin, Palm Beach/FL)

"Blacklist" Acrylic, archival inks, oil paint pens on canvas. 50 x 39" (On Exhibit @ Oditto Gallery, Palm Beach/FL, October, 2022-July, 2023)

SOLD-"60 Years of Nobility" 2022. Acrylic, enamel, oil paint pens, pen & ink on paper collaged on canvas. 48 x 30" (Commissioned by Gary Flom, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia)

"Summer Space" 2022. Archival inks, acrylic, enamel, oil paint pens on canvas. 50 x 39 (On Exhibit in 2023 @ DTR Modern Gallery, Palm Beach/FL)

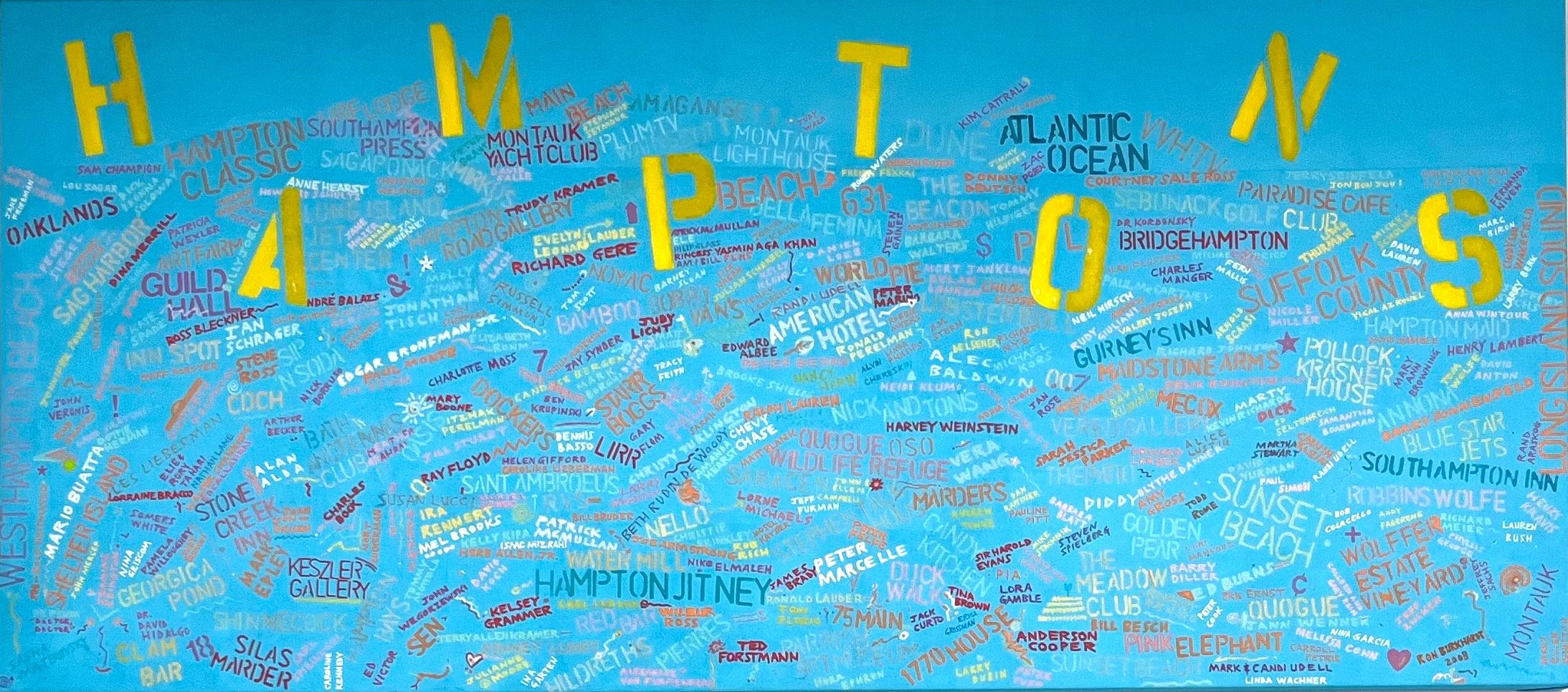

NOTISM: "Hamptons" 2008. Oil paint pens, acrylic, stencils, pen & ink on canvas. 75 x 38" (Historical collection of the artist.)

Notism: "Palm Beach Pandemonium" 2020. Acrylic, oil, pen & ink on paper collaged on canvas. 30 x 48" (On Exhibit @ The Palm Beach Design Showroom, 2021, and The Winter Art Show, 2023, West Palm Beach/FL)

"Notism Dusk" 2022. Acrylic, enamel, pen and ink on paper collaged on canvas. 14 x 11"

"Crimson Tide" 2008. Oil on canvas. 38 x 26" (On Exhibit @ Manolis Projects/Miami, March-September 2022)

SOLD - "Island of Blue" 2017. Acrylic, enamel, oil, pen & ink collaged on paper. 14 x 11" (Private collection of Leticia Gnazz/Palm Beach)

"Notism Dawn" 2022. Acrylic, enamel, pen and ink on paper collaged on canvas. 14 x 11"

SOLD-"Boxed In" 2018. Acrylic, enamel, oil paint pens, pen & ink on paper collaged on canvas. 36 x 24" (Private collection of Gary Flom, Riyadh/Saudi Arabia)

"Mind Orbiting Red" 2023. Acrylic, oil paint pens on canvas. 54x39"

"Corona Crisis in Capricornus Constellation" 2020. Acrylic and oil on canvas. 40 x 16" (On exhibit @ The Palm Beach Design Showroom/Lake Worth, 2022)

"Final Destination" 2003. Pen, Ink, Acrylics and Found Objects on Collaged Board. 30 x 25" (Winner of Medici Medal for "Mixed Media/Installations" at Biennale Internazionale Dell'Arte Contemporanea, Florence/Italy, December, 2005)

"Elements Corrupted" 2007. Oil and stencil on canvas. 48 x 48"

"Refrigerated Notism" Acrylic, oil, oil paint pens on refrigerator door. 85 x 37" (Winner of Medici Medal, Biennale Internazionale Dell'Arte Contemporanea, Citta di Firenze, Italy, 2005.)

SOLD-"Florida Sunsets" 2023. Acrylic, oil paint pens, pen and ink on paper collaged on canvas. 14x11" (Private Collection of Dede Lyons, Palm Beach Gardens, FL

SOLD-"Barbaro's Derby" 2006. Acrylic, enamel, oil paint pens, wrist-bands, ticket stubs, magazine & newspaper articles collaged on canvas. 36 x 48" (Private collection of Bellaria Condominiums/Palm Beach)

Notism: "A Week In The Life" 2006. Acrylics, Enamel, Pen & Ink on Collaged Canvas, 48 x 36" (On Exhibit @ Marion Meyer Contemporary, Laguna Beach/California, November, 2008)

"Hollywooding" 2008. Oil Paint Pen, Ink and Acrylics Stenciled on Canvas. 36 x 72.5" (Exhibited @ Hampton Road Gallery, Southampton/NY, July, 2008, and at Land Rover Gallery, US Headquarters Gallery, New York/NY, December 2008)

SOLD-"Mann House" Acrylic, oil paint pens on paper 18 x 24" (Private collection of Charles Mann III, Atlanta, GA)

SOLD-Notism/Docu-Series: "The Fall of Tinseltown" 2005. Acrylics, enamel, newspapers, Frederick's of Hollywood bra, dollar bills, tinsel, plastic rose and found objects glazed on collaged canvas. 60 x 48" (Private Collection of Terence Robinson, Toronto)

"Green Feathers" 2015. Acrylic, enamel, pen & ink on paper collaged on canvas. 12 x 9"

"Obscured by Basel" 2010. Acrylics, enamel, magazines, cards, airline tickets, sand, pen & ink on paper collaged on canvas. 48 x 36"

SOLD - Style Over Substance: "Against the Grain" 2008. Acrylics and enamel on newspaper collaged on canvas. 36 x 36" (Auctioned @ Sothebys, New York/NY, September, 2009. Private Collection of Childrens' Cancer and Blood Foundation, New York/NY)

"Notism/Primeval" 2004. Acrylics, pen & ink on paper and found objects on collaged canvas. 36 x 48"

"Basel. Art Basel." 2007. Acrylics, enamel, pen & ink, memorabilia, maps, wrist band and found papers collaged on stenciled canvas. 36 x 48"

Notism: "Bridge to Blue" 2002. Acrylic and pen on paper. 12 x 18" (On Exhibit in Solo Show @ DelrayBeach Public Library, March-December 2021.)

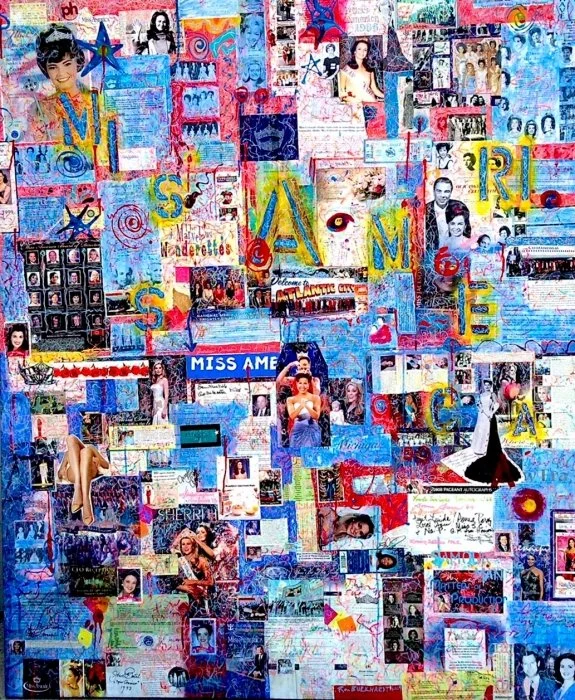

Notism: "Miss America Collage" 2009. Acrylic, enamel, oil paint pens, magazine & newspaper clippings, color xeroxes, memorabilia, ticket stubs, postcards and pen & ink on paper, collaged on canvas. 77 x 50" (For The Miss America Organization. On Permanent Exhibit @ The Hard Rock Hotel/Atlantic City.)

Notism: "Floating Monolith" 2018. Acrylic over pen and ink on paper. 11 x 8.5"

NOTISM: "Walls of Wynwood" 2022. Acrylic, oil, pen & ink collaged on canvas. 20 x 16" (On Exhibit @ The Sovereign Gallery/Wynwood, December 2022)

"Agony20/Ecstasy21" Acrylic, oil paint pen on canvas. 40 x 16" (On exhibit @ The Palm Beach Design Showroom/Lake Worth, 2022)

Notism: "Blind Allegiance" 2013. Oil, acrylics, enamel, pen and ink on paper collaged on canvas. 12 x 16" (On Exhibit @ Delray Beach Public Library Solo Show, March-December 2021)

"Cascades" 2007. Acrylics, pen & ink on Notism paper on collaged canvas. 36 x 48"

SOLD-"First Postings" 1999. Pen & ink on paper collaged in glass frame. 50 x 35" (Private collection of Susan Gavin-Hello, Dallas/TX)

SOLD-Notism/Cityscapes: "Spin City, New York," 2006. Acrylics, pen & ink, and enamel lacquered on Notism papers and collaged on canvas. 36 x 48" (Private Collection of Dr. Alexander Kordonsky, NYC)

SOLD"Black Rainbow" 2007. Acrylic, archival inks on canvas. 36 x 48" (Private collector Greenwich/CT)

"Miami Blues" 2007. Acrylic, pen & ink on paper collaged on canvas. 36 x 48"

"Deconstructed Squares" Acrylic, oil paint pens on paper. 16 x 12" (Private collection of Deborah Kay, Wellington/FL)

"Tucson Skyscape" Acrylic, pen & ink on paper collaged on canvas. 36 x 48"

SOLD-"Mystic City" Acrylic, enamel, pen & ink on paper collaged on canvas. 36 x 48" (Private collection of Congressman Foley, Palm Beach/FL)

"Mercy"

"Bitter Glitter"

"No Vision"

"On the Verge" 2011. Pen & ink and acrylic on canvas. 11 x 8.5"

"Sorrow" Acrylic, oil paint pens on canvas. 12 x 12"

SOLD-"Palm Beach Waterways" 2020. Acrylic, oil, pen & ink on paper (Private Collection of Christopher Fay) 14 x 11"

Style over Substance: "Art and Science" 2006. Acrylics and Enamel on Newspaper Collaged Canvas. 36 x 36" (On Loan to Barbara Kaufman Gallery, Newport Beach/California 2022.)

"Viola FWS" Acrylic, pen & ink on paper.

Style Over Substance - "DNA Swirls" 2006. Acrylics and enamel on newspaper collaged on canvas. 36 x 36" (Exhibited @ DelRay Beach Public Library Solo Show, September-December 2021.)

Style Over Substance: "Volvo DNA" 2006. Acrylics and enamel on newspaper & Volvo green literature collaged on canvas. 36 x 36"

"Split Loyalties" Acrylic, pen & ink on paper collaged on collage. 36 x 48"

SOLD-"Ali" 2005. Acrylic, oil paint pens on canvas. 18 x 36" (Private collection of Muhammad Ali and the Ali Center / Louisville KY)

"Seeking" Acrylic and stencil on canvas. 28 x 24"

"Notism Numerology" Acrylic, enamel, oil paint pens on canvas.

"AlphaNumeric" Oil and stencil on canvas. 28 x 24"

SOLD-"Mystic Notism" Oil, acrylic, pen & ink on canvas. 24 x 36" (Private collection of Leonard Tourne, New York/NY)

"Square Space" 2011. Acrylic, enamel, pen & ink collaged on canvas. 12 x 12"

"Blue Stalactites" Acrylic and Enamel on Imported Paper. 30x22"

"Art & Soul" Acrylic, pen and ink on paper. 12 x 9"

"Electric Zohar" Acrylic, enamel, oil, pen & ink on paper collaged on canvas. (On Loan to Jeanine Edington, Sag Harbor/NY)

"Blue Bayou" Acrylic, oil paint pens, pen & ink on paper. 11 x 8.5"

"Giants Among Men" Acrylic, enamel, magazines, newspaper clippings about NY Giants' Super Bowl win, pen & ink collaged on canvas. 54 x 70"

"Totem Sky" Acrylic, oil paint pens, pen & ink on paper collaged on canvas. 36 x 12"

SOLD-"Activate Nokia" 2004. Mixed media & acrylic on canvas. 50 x 39" (Private Collection of Charles and Louise Mann III, Atlanta/GA)

"Icons of America" 2009. Acrylic, enamel, magazine and newspaper clippings collaged on canvas. 30 x 40"

"Confidence Cracks" 2008. Acrylic, enamel, oil paint pens, pen & ink on paper collaged on canvas. 36 x 48" (On Exhibit @ Luminarte Gallery, March 2011, Dallas/TX)

"On the Edge" Acrylic, archival inks, pen & ink on paper collaged on canvas.

SOLD-"Cacophony" 2008. Acrylic, pen and ink on paper collaged on canvas. 24 x 36" (Private collection of Robert Hernreich Vail, CO)

"Blue Semiotics" 2007. Acrylics, enamel, pen & ink on paper 20 x 16"

"Silent Night" 2007. Oil and candle on canvas. 40 x 30"

"Alzheimer's Affliction" 2008. Oil and acrylic on canvas. 48 x 36"

"Abundance Reigns" 2004. Mixed media, archival inks on paper. 28 x24" (Private Collection of Robert Barker, New York/NY)

SOLD-"Fort Worth Symphony/Painted Violins" (Commissioned by Fort Worth Symphony for charity auction. Private collection of Dr. Gavin) 2008.

More on Notism:

Burkhardt tracks our days through Memory Fragments as we wrestle with the inevitable loss over time of “what we knew, and who we were.” No sooner do we experience “Now” than that moment starts to recede, leaving us facing a nostalgic void for the fading experiences and people no longer near to us, as we desperately strive to keep those memories alive.

This unique genre of contemporary American art fuses abstract semiotics and organic writing to record symbols, words and cultural artifacts even as they drift slowly into the distant black hole of the past.

Burkhardt’s obsessive assaults on blank space, imbued with his compulsive detail, also depict a city-dweller’s incessant drive to harness the information overload of modern society. His intuitive work confers an ordered power on the daily chaos and confusion of our multi-tasking, computer-driven world.

Notism exalts the power of private thoughts expressed in hand-written text–its style, texture, intensity, dynamism, aestheticism, and the primal exuberance of precious memory recall.

These paintings and concepts also connote the eventual non-existence (“not-ism”) of life as it drifts slowly into the distant black hole of the past. Even as our memories and achievements surround us with grace and aesthetic richness.

Burkhardt’s work documents the last vestiges of human writing and its attendant beauty. Its mysterious, spiritual qualities reveal symbolic shapes and forms while exploring common chords in us all.

Working in his idiosyncratic system of “notes as substrate” for over three decades, Burkhardt’s Notist art is both primitive and evolved. The spontaneous, high-voltage images are a testament to the complexity, speed and intensity of modern urban life, with its disparate pulls on one’s soul.

BURKHARDT BREAKS NEW GROUND. LITERALLY.

-Bruce helander 2010

Ron Burkhardt is a consummate bi-coastal artist, who has a literal great gift for calligraphic gab, expressed in symbols and marks on canvas with an assemblage style that’s truly unique. As a man who has outworn and outpaced many creative hats, most notably as an inventive advertising executive and later as a painter of subliminal communicative works, which he invented over time and labels “Notism,” Ron takes the best of his creative experiences and throws out a curve ball at the viewer that spins a curious personal tale with cryptic messages incorporating his own daily schedule wrapped into one.

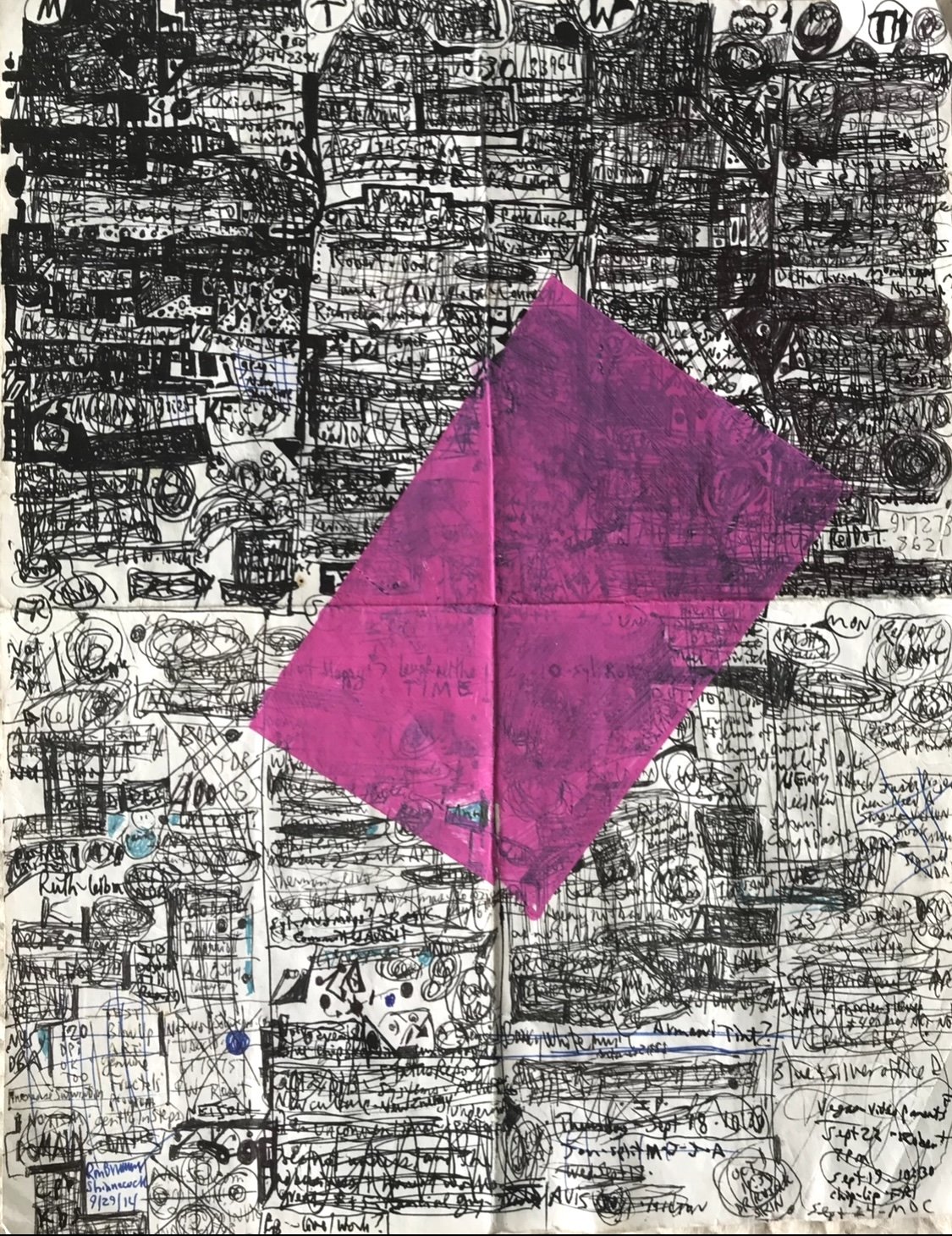

In his latest series, the artist has adopted a “green” approach to art-making by adaptively re-using multi-folded white pieces of stationery that he keeps secluded in his jacket pocket. In one section there might be a reminder about a museum opening, in another a date with a curator and an exhibitions committee. Only the artist himself, like Picasso and Giacometti with their penchant for illegible notes, can fully decipher the doctor’s prescriptive scratchy codes and numerical figures that don’t add up for a common bystander. In some areas, geometric columns have been staked out for days of the week and then sub-divided into hours of the day, only to be eventually crossed off with exuberant scribbles that Cy Twombly would be proud of. At first glance, the written words seem to be the gentle graffiti of a mad man’s fantasy chronicles, until with a smile you discover “things to do” notes about pool furniture, stretcher bars and a Sunday brunch in the Hamptons. At the week’s end, the artist unfolds his personal tales of life and adventures and attaches this post-modern diary to canvas, where he over-paints and embellishes the disappearing calendar of events and visual symbols that are creatively sealed with a transparent wash like a public time capsule at the National Archives of the Smithsonian.

In 2009, he again broke through with his new “Earth Art” series. A total contrast with Notism, these works are devoid of words and scribbles and instantly resonate with our current subdued, economic times. A metaphor for the disintegration of beauty and all things temporal, Earth Art strikes an organic chord that “all glory, and all beauty, is fleeting.” In some cases, he actually allows the canvas to begin deteriorating to convey that we can never conquer nature. Burkhardt travels to hot climates where he places canvases outdoors and alternatively soaks (with rain water), paints and bakes them in the sun, fusing raw dirt into the art’s surface. This weeks-long process creates stunningly unique textures and color palettes, further cementing his status as one of our most original, conceptual artists.

–Bruce Helander is an artist, critic and curator with collages in the permanent collections of over fifty museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Guggenheim, and the Whitney Museum of American Art.

ONE MAN’S BABEL: THE NOTISM OF RON BURKHARDT.

-Peter Frank 2006

We think we know where writing ends and art begins – in calligraphy, a form of manual notation refined by Zen monks, Sufic scribes, Talmudic scholars and Celtic bards into a visual form of transcendent meditation. But writing also transforms into art through what might be the opposite process: a dissolution into the idiosyncrasies of the single mind, the elaborations and accretions of individual hands as they convert thought into script. We associate calligraphy born of such apparent chaos with the unsophisticated, the untrained, even the unhinged; but people who walk comfortably in the world, successful professionals and merchants, policymakers and artisans write, even idly doodle, with a compelling line, an intriguing sense of density, and an intricate grasp of the relationship between word and image. Your writing and mine, after all, descends from pictographic scripture; all writing begins as picture-making, things translated into symbols, ideas given rudimentary form. We always look at writing.

Given his own orientation to the visual, an orientation he honed professionally and personally, Ron Burkhardt could not help but regard writing as something seen, not just read. Like the rest of us, he has generated volumes upon volumes of manual scripture, much of it incidentally But unlike the rest of us, Burkhardt has gone back to these haphazard, offhanded notations and looked at them, too. And he has gotten past what they say, to how they say it – and past that, to how they appear in the act of saying. Most of us would discard our sequences of phone numbers, our memos, the fragmentary notes that clutter our desks and our lives. But Burkhardt follows the lead of the assemblagists who have toiled for a century to recycle the discards of civilization into art: he compiles his myriad scratches into composite, crazy-quilt drawing-paintings.

Slyly arrogating to himself the pretenses of his modernist forebears, Burkhardt calls the resulting visual glossolalia “notism.” Where once mighty movements of modern art came together under rubrics appended with “ism,” indicating common cause among disparate minds, now those minds regard themselves as too disparate to sign manifestoes, and only critics and curators can lump them together. So Burkhardt has forged his own “ism” – one, it turns out, with an impressive pedigree. Miró, Klee, Cy Twombly, Basquiat, and Jean Dubuffet could all have been “notists” avant la lettre (as it were) and the madmen and -women whose obsessive conjurations Dubuffet championed as art brut could well be the foot-soldiers of Burkhardt’s movement. Still, the category does not define the entire oeuvre of any of these artists – not even Burkhardt’s.

It does define Burkhardt’s most distinctive work, those paintings, drawings, and of course collages of his that form a coherent conceptual as well as visual body of work, one distinguished by practice and equally by style. After all, the scribbling that constitutes Burkhardt’s notisseries is his and his alone; for all the extraneous material that finds its way into many of these works, the only handwriting thus engaged, the only manual contribution to these dense skeins of line and image and line-as-image, is Burkhardt’s and Burkhardt’s alone. This singularity of source does not simply affect our regard for the works’ authorship; it affects the look of the works themselves, the consistency of the rhythms and textures that drive the works, that make them so compelling to us. Sure, some of us are prompted to get in close and see whose names – and, if possible, numbers – Burkhardt has cited. But that’s not the content of the art; hell, it’s just barely the content of the artist’s life. The art concerns not what Burkhardt once wrote, but how he once wrote it, and how he’s now woven it back together into a whole.

It’s hardly a seamless whole, and it’s not meant to be; every stitch and join between the lines becomes part of the optical verbiage, and “notism” reveals itself as a Frankensteinian process, its inexactitude a crucial part of its beauty. Notism is neither a whole nor a sum of parts; it is an exploration of how one can become the other, in either direction – how a collection of parts can be fused into a whole, and how our regard for that whole can be a matter of zooming in and out of those parts, looking at the same time for information, no matter how trivial, and the sheer thrill of the line, no matter how tiny. Burkhardt’s real struggle is always against entropy; but the notist artworks never fall back apart, neither flaking off the wall nor melting conceptually into the telephone-pad yammerings they once were. Burkhardt won’t let them – and neither, finally, will our eyes.

Peter Frank/Los Angeles

December 2006

(Peter Frank is art critic for Art News, Angeleno, LA Weekly and Senior Curator at the Riverside Art Museum in California)

BURKHARDT DISCOVERS THERE’S ART IN TAKING NOTES

-Dr Roberta Carasso 2005

ndividual handwriting–a form of intimate drawing, its strokes, rhythms, symbols, erasures and personal touches–are becoming rare. Replaced by electronic writing, mail calendars, online forms, bill paying and receipts, a wide chasm has evolved between individual writing style and electronic writing, between the individual and computerized communication.

Ron Burkhardt has coined the word “Notism,” the modern phenomenon of handwriting as relic. The birth of Notism began when he created, on a sheet of blank paper, a diary of notes of what he needed to do each day, people he needed to see, phone numbers, addresses and whether tasks were completed. Writing in whatever pen or pencil was handy; each page became an organized but free-spirited conglomeration of colors, scrawls and designs. Burkhardt developed a personal history of his days, his thoughts, and his individual, spontaneous way of tackling the mundane and necessary activities…

“Graphololia” is reminiscent of a Jackson Pollock. On a blackboard black background, Burkhardt covers the surface with words and scrawls in thin fluorescent pinks and yellows. The result is primitive and naive, resembling graffiti or the discovery of the first writing. Linear rhythms move in all directions, overshadowing the writing that is there but needs to be discovered.

In “Mystic City,” Burkhardt arranges rectangular papers in a vertical/horizontal Mondrian Constructive pattern….But Burkhardt has no intention of turning these papers into a realistic scene. He intuitively designs each canvas, but always in the framework of contemporary examples of writing. The visual environment is primarily a setting in which he fills the canvas with notes, making the shapes and arrangements they form when placed in a cauldron of letters, the subject of his art.

“Mind Orbits Matter” is boiling with energy. Fragments of pages, painted different colors, exist in a visually explosive field of shapes, colors and lines. Burkhardt has an intuitive knack for placing shapes and injecting them with energetic colorful patterns. The freshness with which he approaches his work gives the impression that each painting is his first.

He creates in both Laguna Beach and New York.

Dr. Roberta Carasso/Elected Member International Art Critics Association

Review Published in Orange County Register–April 14, 2005